Far beyond the planet Neptune, at the edge of the solar system, a mysterious collection of distant worlds can be found hiding in the darkness. These are the worlds that have only been discovered in the last few decades or so. These are actually our solar system’s small wonders, the distant and icy dwarf planets.

In 2006 the international astronomical Union or IAU made a highly controversial decision to place Pluto into a new category, making it the first of the Dwarf planets. This, as many of you reading will agree, did not go down well, and still to this day, some continue to consider Pluto as the solar system’s ninth major planet.

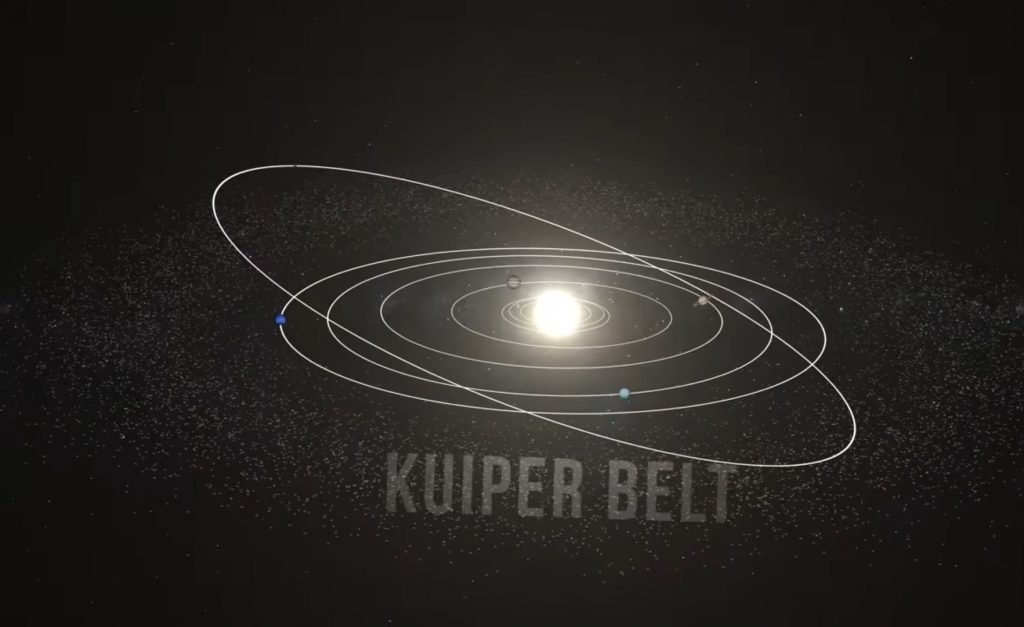

One of the reasons Pluto was reclassified, according to the IAU, is because it hasn’t cleared its neighbourhood. It still shares its space with many other objects in a distant region called the Kuiper belt. In the above image, the doughnut-shaped area just beyond the orbit of Neptune consists of comets, asteroids, and many other Pluto sized objects. Meaning that Pluto is far from alone in the Dwarf planet category.

But how many more of these icy wonders are lurking out there, and how many of them have been officially confirmed as dwarf planets? Currently, the IAU officially classifies only five celestial bodies in our solar system as dwarf planets. Astronomers have, however, identified many other objects that are being considered for the category, and it’s even estimated that hundreds or possibly thousands more may exist, scattered throughout the distant regions of the solar system.

What these elusive worlds look like is still a mystery. Most of the images we have of them show only grainy white dots. But due to the success of the New Horizons mission, we do at least know precisely what Pluto looks like, and so other dwarf planets found throughout the Kuiper belt may share similar features.

The only other confirmed dwarf planet we have closely photographed so far is Ceres, which exists within the inner solar system, between Mars and Jupiter, in an area called the asteroid belt. But to really see how bizarre dwarf planets can be, we need to travel beyond what we have already explored, deep into the icy fringes of the solar system.

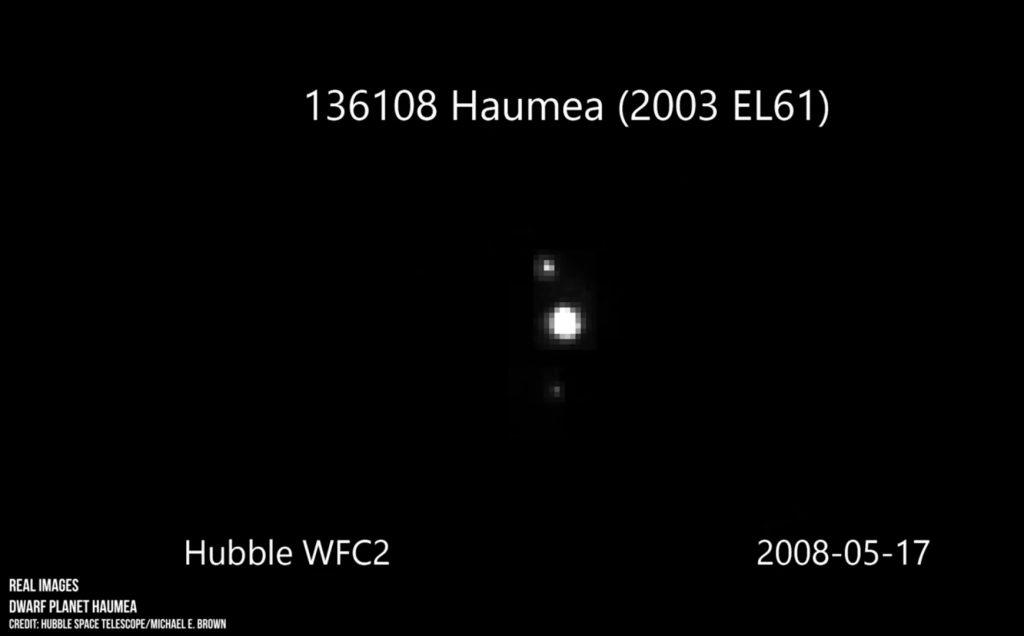

Discovered in 2004, the above unusual egg-shaped dwarf planet has been named Haumea. Everything that we know about Haumea has come from observations made via Hubble and ground-based telescopes back on Earth, and below is the best image ever taken of it.

Haumea is 43 times as distant as the Earth is from the Sun, and to give you an example of how far away that is, it takes sunlight approximately 8 minutes to reach Earth, whereas to reach Haumea, it takes 6 hours. The unusual shape is thought to be a result of its rapid rotation, which distorts Haumea into an oval rather than a sphere, giving it that deformed egg-shaped look. It is one of the fastest spinning large objects in the Solar System, completing one rotation in only 4 hours, which means that one day on Haumea is only 4 hours long.

The strange ring surrounding it is made up of icy debris and was discovered when the dwarf planet passed in front of the light of a distant star in 2017 and orbiting Haumea, you will also notice two small moons named Namaka and Hi’iaka. What caused Haumea to spin so rapidly and gain an icy ring is still a mystery, but scientists think that it may be the result of a large collision that occurred billions of years ago.

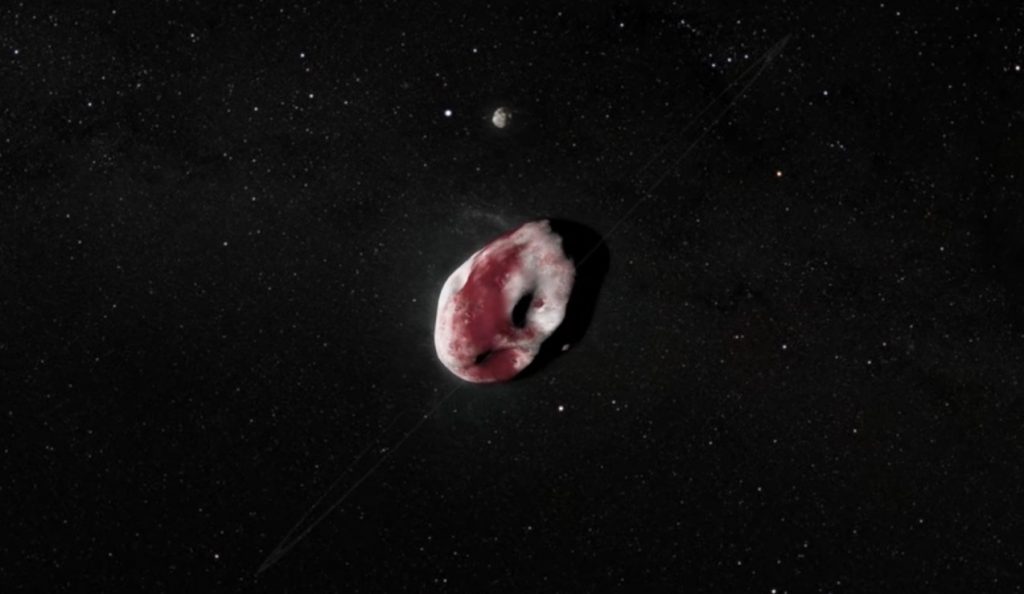

Haumea isn’t the only official dwarf planet lurking in Pluto’s neighborhood, however, because there is an impressively bright object that has also been discovered. Pluto is the brightest object in the Kuiper belt visible from Earth, but the second brightest in this region is the mysterious red dwarf planet named Makemake.

First observed in 2005, Makemake holds an important place in the history of the solar system because it was one of the worlds discovered that prompted the IAU to reconsider the definition of a planet and create the group now known as the Dwarf planets.

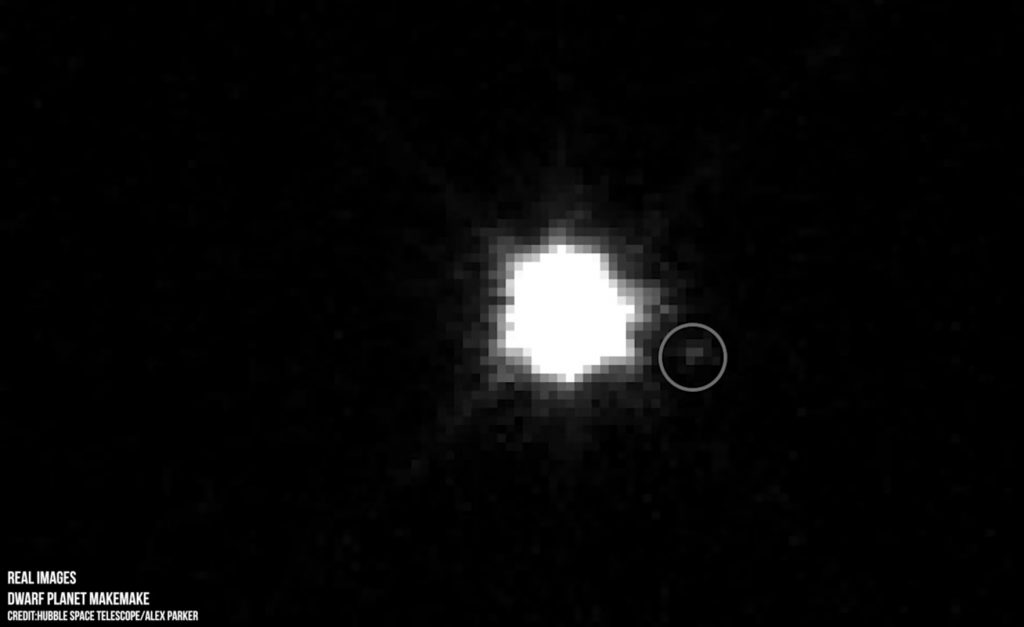

Very little is known about Makemake, but It does appear to be a reddish-brown colour, similar to parts of Pluto, suggesting that its surface is covered in frozen methane and ethane, possibly in the shape of small pellets. Like Haumea, Makemake has never been observed at close range due to its incredible distance from the Sun, a journey that takes light 6 hours and 20 mins to reach it.

The above image taken by Hubble is one of the best views we have of the distant dwarf planet, and although it doesn’t reveal much, if you look carefully, there is another mysterious object barely visible just above the bright dot that is Makemake. This faint dot is a tiny, dark moon nicknamed MK2 that evaded detection for more than a decade, hiding in the glare of its parent. To get to the next and last official dwarf planet, we need to travel even further, all the way to the edge of the Kuiper belt.

Discovered in 2005 by the same team that discovered Makemake, this dense dwarf planet named Eris was briefly thought of as the 10th planet in the solar system. Because of Its striking similarities to Pluto, the discovery of Eris ended up playing a large role in the eventual reclassification of Pluto’s planetary status. A debate that, as I mentioned before, still continues today in the science community and in public.

Some of you may agree more with an earlier plan to increase the number of planets in the solar system from nine to twelve. Seeing Pluto and its moon Charon recognized as twin planets, and Ceres and Eris granted entry to the major planet category. But that early idea was met with opposition, and so the dwarf planet classification was eventually created.

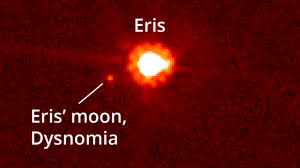

Eris is estimated to hold around 28% more mass than Pluto, despite being smaller in size. It is the farthest officially confirmed dwarf planet from the Sun, located on the outer edge of the Kuiper belt, in a region called the scattered disk. It is so far away, in fact, that it takes sunlight more than nine hours to travel to this mysterious world. Since Eris is so far away, no surface details can be seen, but astronomers have detected the presence of methane ice and believe Eris would likely look something similar to Pluto.

The above image taken by Hubble reveals that Eris also has at least one moon, named Dysnomia, the second-largest moon to a dwarf planet, after Pluto’s Charon. As it stands, the IAU officially only recognize Pluto, Ceres, Haumea, Makemake and Eris as dwarf planets. There are, however, four more mysterious objects that the majority of the scientific community recognize, but are not yet officially confirmed. These are Orcus, Sedna, GongGong and Quaoar.

With newer technology becoming rapidly available and exploratory missions gathering more data on the solar system, our understanding of dwarf planets is slowly increasing. Whether Pluto, Eris, or any other dwarf planet discovered so far should or shouldn’t be classified as a true planet means nothing when you begin to discover how fascinating these small wonders beyond Neptune can be. But one thing is for sure, the discovery of dwarf planets such as Haumea, Makemake and Eris prove that Pluto isn’t the only fascinating world in the Kuiper belt that deserves a future visit.